Probing the early universe using small-scale structure

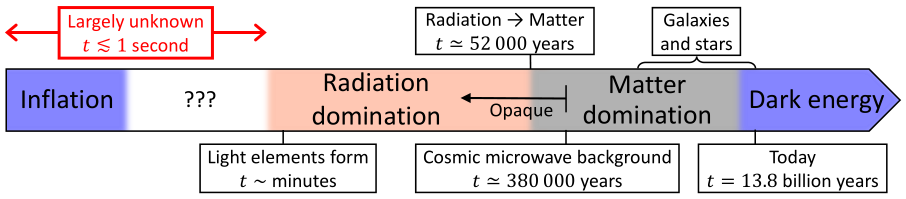

In the very first second, the Universe is thought to have undergone a period of accelerated expansion. During this cosmic inflation, tiny quantum fluctuations expanded to much larger size, seeding initially minor variations in the density of the Universe. Subsequently, regions that were slightly overdense attracted surrounding mass, becoming still denser and eventually growing into the galaxies that we see today. Inflation solves several problems in Big Bang cosmology, such as why opposite corners of the sky have the same temperature despite never coming into causal contact. However, we have little guidance as to how inflation happened, why it ended, or how the familiar forms of matter came to dominate the Universe afterward. The Universe’s first second is largely unprobed.

Fortunately, there is a window into this epoch: the density variations seeded during inflation are sensitive to the physical processes occurring at these early times. The largest-scale fluctuations have been precisely measured using the cosmic microwave background—relic light from the early universe—and observations of large-scale cosmic structure. However, these scales, which are far larger than a galaxy, reflect only a small fraction of inflation’s dynamics. Many inflationary models predict that smaller-scale fluctuations are amplified in characteristic ways. Moreover, there are multiple theories as to how the Universe’s composition evolved after inflation into what it is today. Some of these theories, such as the possibly that the Universe was transiently dominated by an unstable heavy particle, also predict boosted small-scale fluctuations.

Fortunately, there is a window into this epoch: the density variations seeded during inflation are sensitive to the physical processes occurring at these early times. The largest-scale fluctuations have been precisely measured using the cosmic microwave background—relic light from the early universe—and observations of large-scale cosmic structure. However, these scales, which are far larger than a galaxy, reflect only a small fraction of inflation’s dynamics. Many inflationary models predict that smaller-scale fluctuations are amplified in characteristic ways. Moreover, there are multiple theories as to how the Universe’s composition evolved after inflation into what it is today. Some of these theories, such as the possibly that the Universe was transiently dominated by an unstable heavy particle, also predict boosted small-scale fluctuations.

In order to probe the origins of matter and structure in the Universe, my research aims to extend our view of the primordial mass distribution to subgalactic scales. Variations in the density of ordinary matter were washed out at these scales by complex processes, such as star formation. However, it has been well established that ordinary matter accounts for only a small fraction of the Universe’s matter content. The rest of the matter is “dark”: it does not interact with light, so it is exposed to fewer physical processes. Fluctuations that were erased in the ordinary matter are expected to persist in this dark matter. While dark matter is difficult to directly observe, dark matter density variations still manifest in detectable ways. Regions with excess density collapse to form highly dense, gravitationally bound clouds of dark matter, or halos. Galaxies lie at the centers of the largest halos, but sufficiently extreme small-scale density excesses could form minihalos long before galaxies appear. Since they form during a much denser epoch, these minihalos would be extraordinarily dense. If dark matter originated in matter-antimatter pairs—one of the most credible explanations for its prevalence—these pairs would annihilate into detectable radiation today at a rate that is drastically boosted by the high density inside minihalos. Independently of the dark matter model, dense halos can also be detected through their gravitational signatures. My research deciphers the connection between minihalos’ observable characteristics and the properties of the small-scale density variations that formed them, thereby opening a window into these primordial variations that could shed light on inflation and other processes occurring during the Universe’s first second.

Related Publications

- Limits on early matter domination from the isotropic gamma-ray background (2024)

- Simulations of gravitational heating due to early matter domination (2024)

- How an era of kination impacts substructure and the dark matter annihilation rate (2023)

- Lensing constraints on ultradense dark matter halos (2023)

- Ultradense dark matter haloes accompany primordial black holes (2023)

- Dark matter microhalos in the solar neighborhood: Pulsar timing signatures of early matter domination (2022)

- Breaking a dark degeneracy: The gamma-ray signature of early matter domination (2019)

- Annihilation signatures of hidden sector dark matter within early-forming microhalos (2019)

- Density profiles of ultracompact minihalos: Implications for constraining the primordial power spectrum (2018)

- Are ultracompact minihalos really ultracompact? (2018)